Performer: Bhim Biswa

Art Form: Adhunik music

Region: Bhutan/Nepal

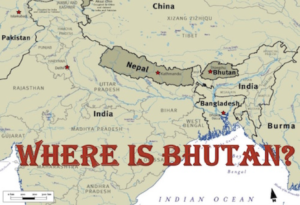

Until 2008, Bhutan was a Buddhist kingdom located between China and India. It is considered to be one of the world’s most isolated countries. Its government enforced a strict cultural regulation policy to limit the influx of foreign influences, including tourism, in an effort to preserve the country’s Buddhist culture. Until the 1960s, the country did not have electricity, paved roads, cars, telephones or a postal service. Only during the late 90s did it begin to allow access to television and the Internet. In the early 1990s, however, with the aim of ensuring a homogenous culture, Bhutan stripped the ethnic Nepalis residing in Bhutan of their citizenship and forced an estimated 108,000 (registered) refugees from southern Bhutan into seven camps in eastern Nepal. These 100,000+ people in camps made up roughly one-sixth of the population of Bhutan.

Homes in these camps were small huts with bamboo roofs, dirt floors and no running water. Camp conditions are on record as having improved between 1995 and 2005, but initially many of the people relocated to these camps succumbed to malnutrition and diseases. In addition, the Bhutanese refugee population was denied the privileges of citizenship in Nepal and was only granted limited access to work opportunities.

In 2000, Bhutan and Nepal agreed to allow some Bhutanese refugees to return to Bhutan, but due to inhabitants who were born in the Nepalese camps not having established Bhutanese citizenship, they were denied repatriation. In 2007, a core group of eight countries came together with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and offered to help resettle Bhutanese refugees from the seven camps to allow them to begin new lives elsewhere. By 2015, it was reported that just two camps remained and the refugee population stood at less than 18,000 people.

Bhim Biswa, who resettled in Syracuse in 2009 recalled his personal experience of resettlement during an interview conducted in November of 2017: “I am from Bhutan, Bhutan is my country. We are Bhutanese Nepali. For political reasons…more than 100,000 people were taken out of the country. We ended up coming to Nepal and became a refugee camp. We lived there for twenty years. Then we tried to go back to Bhutan, Bhutan didn’t let us in. We didn’t have a place to go, then an international organization came and said we’d like to resettle you. So many people went to Canada, USA, Denmark, New Zealand, Australia, so… we are divided. But more than 60,000 came to USA.”

When asked about the tension between Bhutan and Nepal, he stated matter-of-factly that “Nepal is Nepal, a different country. We are not from Nepal, we are from Bhutan. Only we talk the same language but we are Bhutanese, not Nepalese. So, we are kept in the refugee camp, we are isolated. They really hate us.” Having spent nearly twenty years of his life growing up on a refugee camp, throughout our interview he expressed an incredible amount of gratitude for having been allowed to be resettled in the United States: “So as we come here today, tomorrow we got the same rights. Same opportunity like everyone.”

My interview with Bhim took place inside of the home recording studio he has built in the basement of his family’s home in North Syracuse. The tour of his studio began with a demonstration of the madal drum, the first instrument he’d learned to play. The madal is a small two-sided hand drum held sideways in the lap while seated. One of its heads (the “male” head) is larger than the other (the “female” head.) The smaller or “female” head produces a ringing tone when struck, and is typically tuned to the tonic note of the music being played.

Bhim began learning music by playing with like-minded friends living in a refugee camp. “In 1995, I was like teenager. At that time, it was really difficult. We didn’t even have a guitar, no teacher at all.” His first experiences of making music were playing the madal in a group called the Druk Youth Band. “Druk,” he explained, “is a beautiful word for the Bhutan.” Over years spent practicing music with the youth group after school, he learned to play bass guitar, drums, harmonium, piano, then guitar. He stressed that the group’s music making experience was “not something we learned from teachers, we learned from each other by hearing. I don’t know notation or anything.”

While some may view a lack of formal musical training as a handicap, Bhim values the hands-on approach he took to learning music. Despite not having taken lessons, he is more than willing to provide lessons and teach kids to play guitar or drums. He stated that he has developed a teaching method which minimizes theory and maximizes the enjoyment of making music. “Teach them that [music making] can be fun,” he says, “and encourage them to play.”

Participating with a Christian youth organization while in Nepal resulted in Bhim being granted an opportunity to participate in recording projects. He was invited to play guitar and sing on recordings. The experience of recording in a simple multitracking studio seeded the dream of eventually having his own recording studio, where he could compose his own musical arrangements. “My first time recording,” he joked, “we recorded to a seven-track tape recorder.” Several years later, and thousands of miles away from where he’d first begun playing music, he is now fully equipped with the means of recording multitrack arrangements, and collaborates with local musicians as well as friends located in different regions throughout the U.S.

He demonstrated a number of his recordings, introducing the style as adhunik music, a modern variety of Nepali romantic pop music which gained popularity on Nepalese radio in the 1990s. He described his ideal musical production as “music that the people will like,” explaining that “some younger people enjoy pop music while older people enjoy the folk-styled music,” and that he strives to compose and record music which resonates with a majority of the Bhutanese people. His music’s lyrics, he explained, are a reflection of his gratitude and devotion to God, and he beamed with joy while telling me of the blessings he and his family received by way of being given an opportunity to resettle and thrive as American citizens.

Sources

Adelman, Howard (2008). Protracted Displacement in Asia: No Place to Call Home. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 0-7546-7238-7.

Biswa, Bhim. Interview by author. November 12, 2017.

“Bhutanese Refugees Find Home in America”, The White House, 11 March 2016. obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/blog/2016/03/11/bhutanese-refugees-find-home-america

Eisenstadt, Marnie. “From mud huts to $100,000 homes, Bhutanese refugees put down deep roots in Syracuse”, 28 June 2017. “www.syracuse.com/news/index.ssf/2017/06/from_mud_huts_to_100000_homes_bhutanese_refugees_put_down_deep_roots_in_syracuse.html

Shresta, Deepesh Das. “Resettlement of Bhutanese refugees surpasses 100,000 mark”, UNHCR, 19 November 2015, www.unhcr.org/en-us/news/latest/2015/11/564dded46/resettlement-bhutanese-refugees-surpasses-100000-mark.html

Shrestha, Manesh. “First of 60,000 refugees from Bhutan arrive in U.S.”, 25 March 2008. edition.cnn.com/2008/WORLD/asiapcf/03/25/bhutan.refugees/index.html